19 Oct “Sound it out”

“Sound it out.” I’m curious how often this approach actually works for English spellers. I’m thinking it’s not all that often. I’ve read that approximately 50% of English words can be spelled by sound/symbol correspondence, but really? Does that account for phonemes (basically, the sounds of a language) that can be represented with more than one grapheme (the letters that represent phonemes)? <cat> vs <kat>, for example?

What I see in my work with clients is a lot of damage from this advice. I have students who simply can’t let go of using “sound it out” as their primary, and possibly only, tool in their spelling toolbox. And when that happens, they end up with incorrect spellings almost all the time.

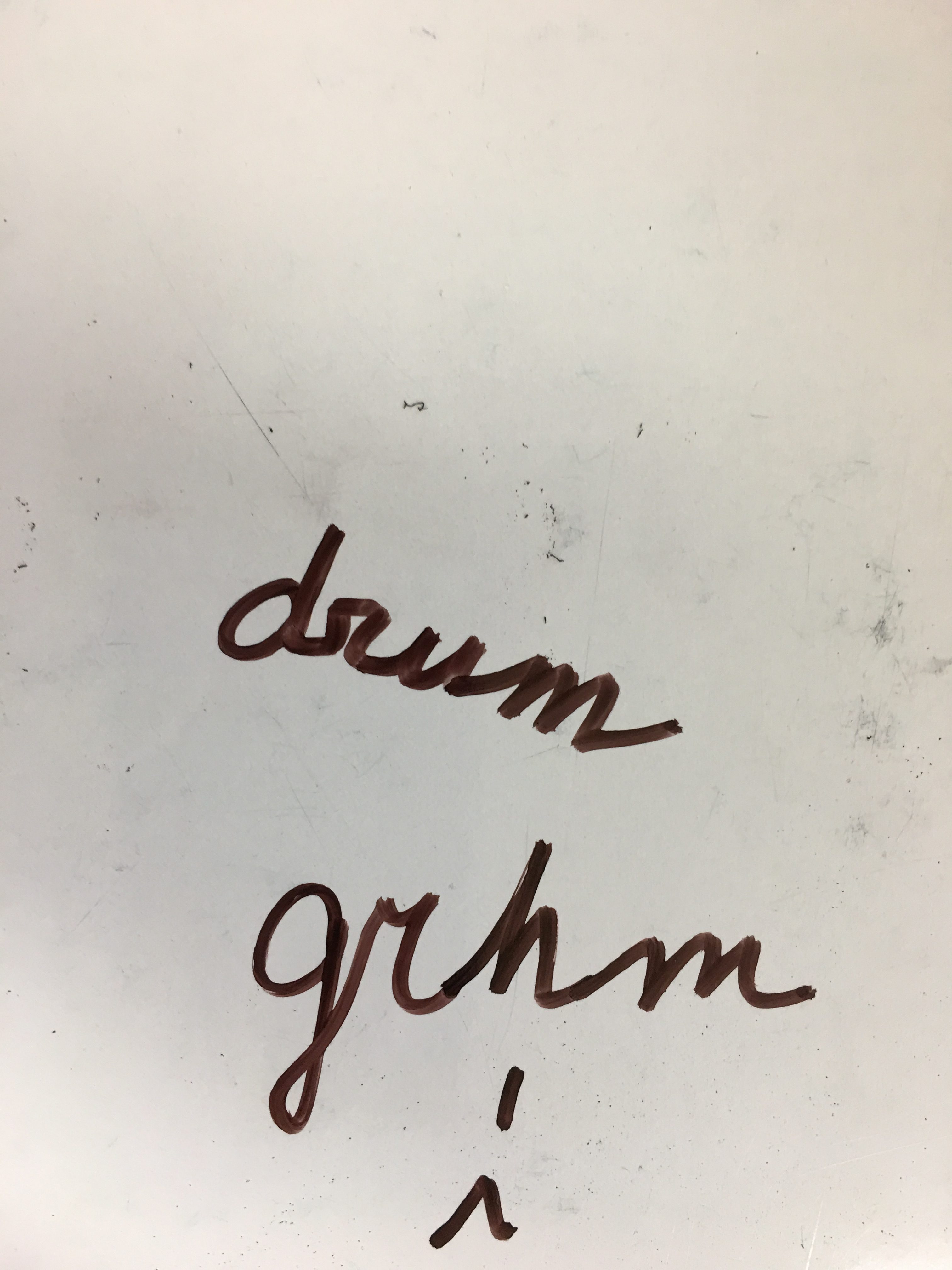

I’m currently working with a second grader who is working hard at reading and writing. When I asked him to spell <drum> for me yesterday, he lost his typical energy and enthusiasm and almost shrunk into himself. I said, “Go ahead, even if you make mistakes, it’ll help me understand how you’re thinking about the word.” He finally consented, but only if I wrote the letters that he said (and this is a student who enjoys writing in cursive and usually wants to do the writing himself). He spelled out <grhm>. From a sound it out perspective, this is completely reasonable. If we stop to think about how we really pronounce the <d> in <dr>-initial words, it’s often more of a “j” sound (/dʒ/). My client represented that with a <g>. Very reasonable. And when he stretched out the vowel, he heard /h/ instead of /ʌ/ (or “uh”*). This is sounding it out. This child is listening very, very carefully to what he’s saying and working very hard to sound it out, and the result is so unsuccessful that my asking him to write a new word changed his entire demeanor.

I have a different student who has been working with me for two years. We have been working for three weeks now on the word “especially”. We first studied the word three weeks ago; she discovered the base was <spece> and that it had an epenthetic <e>, the same <e> that is in <antidisestablishmentarianism>, a word that brings her much joy. We connected the base to other words, such as <speculate> and <species>. We noticed that the <c> represents three different phonemes in these words. She saw that the word “especially” had two suffixes, <al> and <ly> and could tell me that the reason the word had two <l>’s in it was because the two suffixes are next to each other. We discussed the connector vowel <i> and why it’s in this word (it marks the pronunciation of the <c>). She got it. She spelled the word on her own, it was lovely. My student struggles with memory, and so we spend time in our sessions reviewing words we’ve studied previously. It usually takes several sessions to fully wrestle a word into her memory, but they get there. Almost always, her first approach is to sound it out. And it never works. The word “especially” has been particularly hard for her – she simply cannot let go of her years of being told to sound it out. She knows it’s not going to help her find the spelling, but she insists on writing it down as her first attempt *<espshly>, *<esposhily>, *<espishlly>. And then she gets frustrated. She wants to use these spellings as a jumping off point, hoping that when she looks at her writing of the word it will trigger the work we’ve done in previous sessions. But it doesn’t. Because how do you get from “sound it out” to <e+spece/+i+al+ly>?

This is the same client who once asked me, “Why did everyone else lie to me? Why did they teach me all that other stuff?” She now enjoys discovering the myths that are out there, her favorite is the idea that <tion> is a suffix. But on the edges of that pleasure is a deep frustration at the years that were spent learning an approach that didn’t help her.

It’s hard to shift out of “sound it out”. I still wrestle with it. And right now you may be thinking, “But the sounds matter! You can’t just ignore them!” You’re right, they do matter. Please notice in my description of our study of <especially> how often we discussed ‘sound’. We talked about <c> representing three different phonemes. We talked about the role of the connector vowel <i>, and we even talked about that epenthetic <e>, which is there for reasons related to pronunciation. It’s just that we talked about the ‘sounds’ in the context of the word we were studying, as just one of the reasons a word is spelled the way it is.

And so, I encourage you to avoid responding with “sound it out” when someone asks you how to spell a word. Instead, try giving them the spelling in segments that demonstrate the parts of the word, such as “r . ai . n (pause) b . ow”. Or link the spelling to another word they already know. “‘Couch’ uses the same grapheme for /ɑʊ/ that the word ‘house’ does.” Or talk about the base of the word, “‘Eventually’ has the same base as ‘prevent’,” or “The base of ‘eventually’ is <vent>.” I promise your speller will roll their eyes the same way they do when they’re told to sound it out, but they will be gaining a real understanding of English spelling as they do it.

*Please notice that in order to represent this phoneme to those who don’t know IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet, the symbols used the represent the sounds of our language), I had to add an <h> to the <u>. See the connection between these letters and this sound?